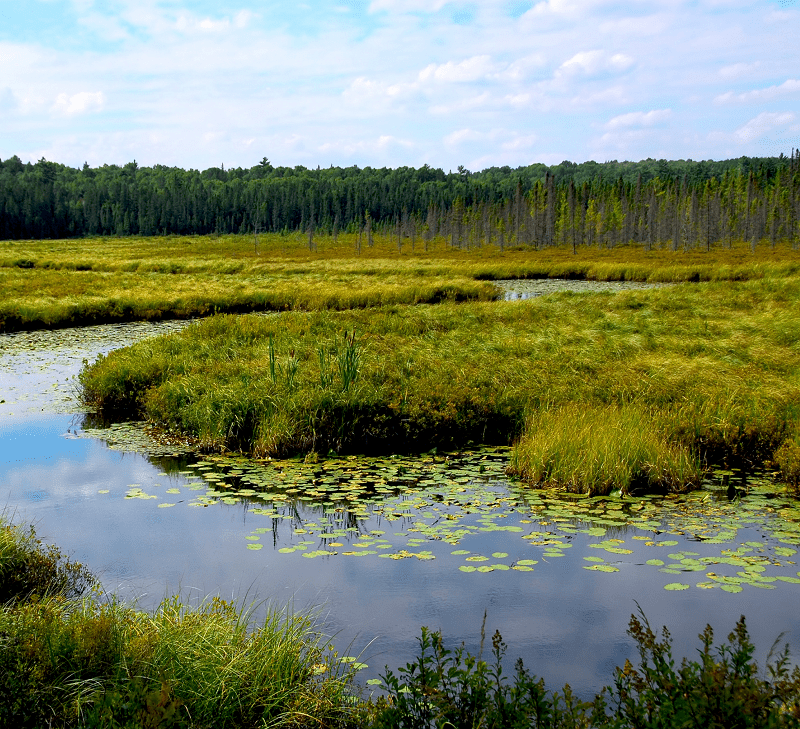

Although the functions that wetlands provide make them our most valuable landforms, the United States and Canada have lost alarming amounts of wetland habitats. According to a study by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lower 48 states have lost over 53% of their original wetlands. Great Lakes states and the province of Ontario have fared worse – it’s estimated that only 30% of the original wetlands remain in the Great Lakes Basin.

There have been no comprehensive studies to document and assess the overall ecosystem impacts of these significant wetland losses. However, one needs only to consider the increases in flood damage, the degraded or impaired lakes and rivers, the number of threatened and endangered species, and myriad other indicators of poor ecosystem health to get an idea of the impacts.

To this day, wetlands continue to be degraded or converted to other uses. Each year, government agencies receive dredging and filling permit or zoning applications to authorize activities that degrade wetlands in the Great Lakes Basin. The vast majority of these permits or zoning applications are issued. On top of this intense pressure, there are numerous other activities that degrade wetlands with little or no regulatory oversight, including drainage projects, polluting wetlands with contaminated runoff, and land clearing and logging. These continued threats to Great Lakes wetlands underscore the critical importance of citizen involvement in protecting them.

Prepared in February 2004 by Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council for Freshwater Future, a project of the Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council. Funding provided by E.P.A. Great Lakes Grants Program, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Copyright 2025 Freshwater Future. All Rights Reserved.